http://diaryofarepublicanhater.blogspot.com/2013/03/what-will-bob-murphy-accuse-krugman-of.html

It's quite amazing the lengths he'll go to to get a gotcha moment on Krugman. To me the argument was totally specious:

"In a post titled, “Debasing Lincoln” Krugman writes:

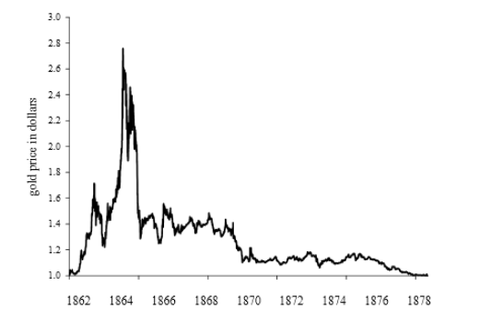

Greg Sargent catches John Boehner invoking none other than Abraham Lincoln to inveigh against the deficit. This is pretty funny — in multiple ways.One is the whole notion of relying on Lincoln as an authority on economic policy. Why should we believe that a lawyer speaking in 1843…knew what we should be doing about an economic slump…170 years later?Then there’s Greg’s catch: Boehner truncated the quote, leaving out the part where Lincoln called for balancing the budget by raising taxes. And also the point that Lincoln was actually a big government interventionist for his time, a strong advocate of what we would now call industrial policy.But wait: there’s more. Lincoln’s most dramatic departure from standard economic policy was … drumroll .. debasing the currency (pdf). Here’s the dollar price of gold:

"Wow, where to begin?"

"First, note the irony here. Krugman is chastising John Boehner for not realizing that Lincoln was a tax-raising, big government advocate of industrial policy, who also debased the currency. And yet, when Tom DiLorenzo was a witness for Ron Paul’s monetary committee, Krugman summarized the episode with a blog post titled “Johnny Reb Economics.” His good buddy Matt Yglesias had an even more inflammatory title, “The Strange Case of Pro-Confederate Monetary Policy.” (In fairness, maybe the editors at ThinkProgress pick their blog post titles.) So it seems if you call Lincoln a big government fascist, you get your head bitten off, and if you cast Lincoln as a small government conservative, you get mocked. Tough crowd, these progressive bloggers."

"But that’s just incidental. The real jaw-dropper in Krugman’s post above, is his claim that “nothing terrible happened” from 1862 to 1878, and that therefore the Very Serious People who worried about Lincoln going off gold are proven wrong once again."

"Naturally, there was the whole Civil War (aka War Between the States aka War of Northern Aggression), with hundreds of thousands of people dying. So obviously the economy was in awful shape during these years."

Gotcha Krugman! You forgot about the Civil War! Next Murphy zaps him for forgetting the Depression of the 1870s:

"Let’s continue, to prove my point. After the Civil War, but when the U.S. was still not back to dollar parity with gold, did we have any kind of economic problems? After all, Krugman’s chart–and his statement “despite 15 years off the gold standard”–show that we need to consider U.S. economic history from 1866 to 1878, if we want to see what the postwar era was like."

"Here’s an interesting idea: Before we look it up, let’s first settle something obvious. If there had been, oh I don’t know, the worst depression in U.S. history to that point, then probably that would count as “something terrible” happening, right? Maybe it wouldn’t be the fault of going off gold, but surely Krugman would be either a liar or ignorant if he said “nothing terrible happened,” right?"

"Well there was this thing called the “long depression,” which the NBER dates from October 1873 to March 1879. Here’s how Wikipedia describes it:

The Long Depression was a worldwide economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running through the spring of 1879. It was the most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing strong economic growth fueled by the Second Industrial Revolution in the decade following the American Civil War. At the time, the episode was labeled the Great Depression and held that designation until the Great Depression of the 1930s. Though a period of general deflation and low growth, it did not have the severe economic retrogression of the Great Depression.[1]It was most notable in Western Europe and North America, at least in part because reliable data from the period are most readily available in those parts of the world. The United Kingdom is often considered to have been the hardest hit; during this period it lost some of its large industrial lead over the economies of Continental Europe.[2] While it was occurring, the view was prominent that the economy of the United Kingdom had been in continuous depression from 1873 to as late as 1896 and some texts refer to the period as the Great Depression of 1873–96.[3]In the United States, economists typically refer to the Long Depression as the Depression of 1873–79, kicked off by the Panic of 1873, and followed by the Panic of 1893, book-ending the entire period of the wider Long Depression.[4] The National Bureau of Economic Research dates the contraction following the panic as lasting from October 1873 to March 1879. At 65 months, it is the longest-lasting contraction identified by the NBER, eclipsing the Great Depression’s 43 months of contraction.[5][6]In the US, from 1873–1879, 18,000 businesses went bankrupt, including hundreds of banks, and ten states went bankrupt,[7] while unemployment peaked at 14% in 1876,[8] long after the panic ended.

"This is simply inexcusable. And as I have taken pains to point out over the years, this is typical Krugman. He simply makes stuff up about the historical “record,” with such carelessness in throwaway lines that when you catch him, his fans won’t even care. To wit: “Oh come on Bob, it’s not like Krugman said, ‘The Long Depression wasn’t terrible.’ All he meant was, Lincoln’s debasement of the currency had no ill effects. The Long Depression wasn’t about gold at all; there was deflation!”

If you think I'm exaggerating that this is all about his obsession with finding a smoking gun on Krugman check out his snarky rejoinder to me and fellow Keyensian Lord Keynes in the comments:

"You guys (by which I mean Mike Sax and Lord Keynes) are awesome. You are actually saying:"

“Sure Krugman’s argument makes no sense at all. But why you think that is somehow a smoking gun that Krugman writes bad blog posts, is beyond me. The earth didn’t cave in when Lincoln went off gold, so clearly the gold standard is stupid.”

He honestly thinks that if he finds the right smoking gun he'll be able to literally destroy Krugman's reputation and no one will ever read his columns or interview him on tv again. As to the gold standard, whether or not you want to call it "stupid" I find today's gold bugs pretty stupid, that much I'll concede.

Daniel Kuehn, a New Keynesian type that often comments at Bob's argues that Krugman was careless in saying "nothing terrible happened despite 15 years off the gold standard" as some terrible things did happen-the Civil War and it's human and economic effects and the 1870s depression. Ie, all these terrible things that did happen during the 15 year period were "noise" and kind of drown out Krugman's point.

I disagree with this. I think what Krugman was getting at was clear enough. As for noise, well, it's up to economists to not allow noise to distract them. Bob is trying to use noise here to distract from the real issues.

Lord Keynes however, brings some actual reality back to the free for all over at Bob's by providing some actual facts about the period. What we learn from him is that if Krugman had felt a need to delve more deeply into the period of 1862-1877 it would actually have strengthened his case considerably. For one thing Krugman may have been somewhat imprecise in calling the Greenback period 1862-1877.

When we delve more deeply into the 1870s period we discover that the depression of the 70s was caused by deep deflation:

" First, if Krugman declared that the greenback era was from 1862 to 1878, then he is wrong, and you would have done better to examine whether his statement was true."

"As Yosef points out, 1873-1879 is hardly to be considered a “greenback” era. It was a deflationary era:

(1) by 1868 the Treasury had already withdrawn $100 million in greenbacks;

(2) the Coinage Act of 1873 was deflationary:

The Fourth Coinage Act was enacted by the United States Congress in 1873; it embraced the gold standard, and demonetized silver. Western mining interests and others who wanted silver in circulation years later labeled this measure the “Crime of ’73″[1]. Gold became the only metallic standard in the United States, hence putting the United States de facto on the gold standard.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coinage_Act_of_1873

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coinage_Act_of_1873

(3) in 1874, “hard money” supporters persuaded Grant to veto a bill to print more money;

(4) in 1875, the “hard money” victory was nearly complete: they got the Resumption Act passed and the

Treasury began to acquire gold reserves by federal surpluses and borrowing to back the greenbacks in circulation, further inflicting a deflationary bias.

Treasury began to acquire gold reserves by federal surpluses and borrowing to back the greenbacks in circulation, further inflicting a deflationary bias.

LK then goes on to point out that Murphy's narrative of this period, interestingly enough, conflicts with Rothbard's who actually claimed, ironically enough that during the 1870s: basically nothing happened, and that the depression of that decade is a myth perpetuated by Keynesian inflationists to libel an era of low prices but no depression.

"It should be clear, then, that the ‘great depression’ of the 1870s is merely a myth—a myth brought about by misinterpretation of the fact that prices in general fell sharply during the entire period. Indeed they fell from the end of the Civil War until 1879. Friedman and Schwartz estimated that prices in general fell from 1869 to 1879 by 3.8 percent per annum. Unfortunately, most historians and economists are conditioned to believe that steadily and sharply falling prices must result in depression: hence their amazement at the obvious prosperity and economic growth during this era. For they have overlooked the fact that in the natural course of events, when government and the banking system do not increase the money supply very rapidly, free-market capitalism will result in an increase of production and economic growth so great as to swamp the increase of money supply. Prices will fall, and the consequences will be not depression or stagnation, but prosperity (since costs are falling, too) economic growth, and the spread of the increased living standard to all the consumers.” (Rothbard 2002: 154–155)."

Good job LK! At least some one is dabbling in actual history rather than historical fiction.